Masters Dissertation

Enhancing Community Physical Activity Referral and Signpost: A Mixed-Method Survey Exploring Resources and Strategies Among UK Physiotherapists

Abstract

Introduction: Despite the wanted shifts in UK healthcare policy towards a preventative agenda and the recognised role of physical activity (PA) in managing long-term conditions (LTCs), referral and signposting practices towards community PA services or information among UK physiotherapists remain inconsistent.

Aim: To identify what resources and strategies UK physiotherapists use to refer or signpost patients with LTCs to community PA services and explore their experiences.

Methods: A cross-sectional design with a mixed-method survey was employed. Quantitative data were analysed predominately using descriptive percentages, and Chi-square tests were used to examine associations. Qualitative data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results: 45 physiotherapists and physiotherapy students from 9 different UK regions participated with mean age (standard deviation) of 37.8 (10.6) years. Thirty-one percent had over 20 years of experience as physiotherapists, 63% were from the public sector (NHS), majority worked in outpatient or community settings, and 84% reported over 50% of their caseload had LTCs. PA prescription was common (93%), but only 49% referred and 51% signposted to community PA. Seventy-six percent referred to community PA in their practice, of which 88% reported they use resources but only 29% reported using strategies to do so. Sixty-four percent perceived their described resource or strategy as moderately effective for PA promotion. Awareness of government-promoted resources and strategies was limited. Participants favoured digital tools, but often combined resources depending on the patient population. Although 20% had positive experiences, most faced challenges when referring and signposting to community PA. Positive themes included opportunity and communication whereas challenges included access barriers e.g., socioeconomic, structural, systemic and knowledge of services and interpersonal barriers e.g., patient motivation and professional accountability. Suggestions to improve practice were to enhance practical resources, communication and interaction between all stakeholders.

Conclusion: The findings suggest a gap between policy-driven PA initiatives and current physiotherapy practice. There is a clear call to action to create better supportive resources and strategies to help physiotherapist implement better referral and signposting practices into practice. Future research should support implementation based on physiotherapist preferences including up-to-date national and regional directories, formal training, and patient-specific tools.

Abbreviation List

Allied Health Professionals (AHPs)

British Medical Journal (BMJ)

Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP)

Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC)

Long-term conditions (LTCs)

Make Every Contact Count (MECC)

National Healthcare Service (NHS)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

Physical activity (PA)

Public Health England (PHE)

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP)

United Kingdom Chief Medical Officers' (UK CMO)

United Kingdom (UK)

World Health Organisation (WHO)

1. Introduction

Prevention is one of the most cost-efficient and effective strategies in healthcare. As such, the National Health Service (NHS) Long-Term Plan (2019) was designed to shift the NHS model towards greater preventive investment. This shift is driven by the rise of non-communicable diseases and ageing populations (Omotayo et al., 2024). It is an ever-growing concern, as one in three people in England live with at least one long-term condition (LTC) (Public Health England (PHE), 2020), resulting in estimated costs to the healthcare service being £115.2 billion (Sloggett, 2023). The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines preventive healthcare as any activity to prevent disease onset, reduce risk, or mitigate its impact (WHO, 1998). Healthy lifestyle choices, self-management and rehabilitation are examples of preventative healthcare strategies that are fundamental in managing and treating LTCs (NICE, 2013; 2016; Vodovotz et al., 2020). Physical activity (PA)—any bodily movement that expends energy—and its structured form, exercise, are central to health promotion and preventative efforts (WHO, 2020; Department of Health and Social Care, 2019) as regular movement, most notably at moderate intensity, supports unique physiological processes that maintain healthy systems and organs (Qiu et al., 2022). As a result, physical inactivity is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases, increasing premature mortality risk by 20–30% (WHO, 2020).

Dibben et al. (2024) conducted an umbrella review combining data from over 936,000 people. They identified clinically meaningful improvements in health-related quality of life and functional capacity from PA interventions across 25 different LTCs – although it is less clear for mortality and hospitalisation data. Sensitivity analysis was not conducted, limiting understanding of whether low methodological quality impacted the pooled effect size results, as only 12% of the included reviews were deemed ‘high quality’ according to their AMSTAR-2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) evaluation. Concerns around PA for those with LTCs, such as clinical safety in heart failure patients, are reasonable, as raised in a qualitative study by Franco et al. (2015). These concerns stem from outdated cultural views that bias ‘rest’ and promote over-reliance on medical professionals, making patients less autonomous in managing their health conditions (Alsop et al., 2023). Experts and systematic reviews have revealed that the benefits of PA outweigh the negatives, even in higher-risk populations (Hopman et al., 2016; Reid et al., 2022). Therefore, the literature over the last decade has become increasingly robust, providing clinical effectiveness despite some nuances around the certainty of evidence.

Unfortunately, in the UK, challenges to PA participation remain significant among those with LTCs due to deficits in capability, opportunity, and motivation — three central pillars of behavioural change (Carstairs et al., 2020; Speake et al., 2021). Community-based services, such as Social Prescribing, offer accessible and low-cost solutions for all patients (Jones and Burns, 2021) and have the potential to reduce pressure on primary care NHS services while improving patient outcomes (Mossabir et al., 2015; NHS England, 2016; The Health Foundation, 2018). However, community-based services often provide only small improvements in health outcomes (Moffat et al., 2023), and real-life implementation challenges persist, including a lack of direct integration of PA into their care pathways. A care pathway is a route of mutual clinical decision-making that identifies specific outcomes for a group of patients who would benefit from organised care. Greenwood-Lee et al. (2018) identified gaps in primary-to-specialty care referral delivery linked to clinical decision-making, information and systems management, and quality monitoring. Others highlighted limited resources, weak infrastructure, and insufficient cross-sector collaboration as key barriers to integration within the health sector (Omotayo et al., 2024). Technology has offered the potential to address these barriers by improving the efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility of referral systems (Flannery et al., 2022). However, adopting such tools remains inconsistent, with many NHS Trusts lagging in digital transformation efforts, traditionally due to a lack of resource allocation and budgeting (Honeyman et al., 2016), and may introduce digital literacy issues (Gavin et al., 2024). Crucially, patients are particularly receptive to community-based services as a solution to primary care pressures, reporting greater control over their health and improved continuity of care across services (Speake et al., 2021). Nevertheless, experiences vary geographically (Moffat et al., 2023).

Frontline healthcare staff have significant public trust compared to other professions (Skinner and Clemence, 2017). Within clinical settings, other healthcare professionals have deemed physiotherapists best suited for PA promotion (Albert et al., 2020). Physiotherapists are crucial in managing and treating patients with LTCs because of their knowledge in rehabilitation and self-management strategies aimed to improve or restore quality of life aligned with the WHO’s definition of preventative healthcare (Dennis et al., 2024; Reddy et al., 2024). The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) Standard 15 outlines that UK physiotherapists must understand their role in health promotion, education, and the prevention of ill health and how the broader determinants of health impact a person's well-being. They must also empower and facilitate individuals to self-manage their health (HCPC, 2023). But how is this translated into practice?

Despite policy intentions around PA promotion, implementation into routine practice has been consistently difficult for many clinicians (Albert et al., 2020; Carstairs et al., 2020; Cunningham and O’Sullivan, 2021a; 2021b; Speake et al., 2021; Parchment et al., 2022; Raghavan et al., 2023; Dunphy et al., 2024), including physiotherapists globally (Freene et al., 2017; Kunstler et al., 2019; West et al., 2021), in the UK (Lowe et al., 2017; Lowe, Littlewood and McLean, 2018; Stead et al., 2023; Wing et al., 2025) and for UK student physiotherapists (Clifford et al., 2018; Wing et al., 2025; Thomas, Wright, and Chesterton, 2025). Williams et al.'s (2012) systematic review found that brief advice in primary care has small but positive effects on PA. Since, Cantrell et al.'s (2024) realist review highlighted wide variation in signposting roles across clinicians, services, and teams, concluding this reflects an ongoing disconnect between policy and its practical application. Literature review revealed several high-quality qualitative and quantitative studies reinforcing these challenges, adding depth and breadth to the phenomenon. Surveys show that physiotherapists widely agree PA promotion is important and falls within their scope of practice. However, referral and signposting to PA opportunities remain limited, often due to poor knowledge of PA guidelines and uncertainty about initiating PA-related conversations with patients (Freene et al., 2017; Lowe et al., 2017; Lowe, Littlewood and McLean, 2018; Clifford et al., 2018; Kunstler et al., 2019; Cunningham and O’Sullivan, 2021b; Wing et al., 2025). Qualitative studies found that physiotherapists' barriers to promoting PA include a lack of time and resources, unclear referral pathways, poor support from leadership and complex patient populations (Lowe et al., 2017; Carstairs et al., 2020; Speake et al., 2021; West et al., 2021; Cunningham and O’Sullivan, 2021a; Parchment et al., 2022; Stead et al., 2023; Raghavan et al., 2023; Dunphy et al., 2024). Notably, improving resources is a recurring suggestion, offering a feasible way to mitigate time-related challenges.

Clinicians often need to balance the delivery of high-quality care with what is feasible in practice. For example, while qualitative studies suggest physiotherapists believe motivational interviewing is more effective than PA resources in engaging patients, the latter is often favoured due to time constraints. Research suggests UK physiotherapists believe there is already ample Public Health information on PA for both clinicians and patients, but its practical application is often overlooked (Moran, 2017). Identified methods of PA promotion in routine practice include direct prescription, referral, or signposting—either passive (e.g., infographics in waiting rooms) or active (e.g., verbal recommendations) (Carstairs et al., 2020). However, few of the above-mentioned studies explored the specific resources physiotherapists use to support referral or signposting practices, nor did they explicitly examine clinicians’ experiences or reflections on these processes. Only one study, by Cunningham and O’Sullivan (2021b), identified broadly defined resources intended to support knowledge development, but it did not address other potential enablers of practical implementation.

This study seeks to address that gap by investigating which resources and strategies are currently used, where barriers remain, and why. It asks: What resources and strategies do UK physiotherapists use to refer or signpost patients with long-term conditions to community physical activity services or information? The aim is to understand current practice better and gather insights into physiotherapists’ experiences of referring or signposting to community PA opportunities. The objectives are to:

1. Identify UK physiotherapists' resources and strategies for referring or signposting patients to community PA services or information, including their familiarity with existing government-promoted resources and strategies.

2. Explore physiotherapist experiences of referral and signposting to community PA.

3. Identify the perceived effectiveness of referral or signpost to community PA and possible improvements.

4. Examine whether demographic factors (e.g., sector, setting, experience, caseload) influence referral or signposting practices.

Findings from this study may help physiotherapists identify alternative resources and strategies, supporting improved referral and signposting practices. This aligns with public health priorities such as the NHS Long Term Plan, the 'Make Every Contact Count' (MECC) initiative, and HCPC professional standards. Furthermore, this research may contribute to wider implementation efforts across teams, Trusts, and national PA promotion policies by identifying what works and where barriers persist.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study Design

This research employed a pragmatic paradigm to conduct a mixed-methods survey, concurrently gathering complementary quantitative and qualitative data. Reporting has been guided by the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS; Sharma et al., 2021) and, where applicable, by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig, 2007). Existing literature on this topic are quantitative surveys or qualitative methods involving interviews or focus groups. In public health, cross-sectional studies are often employed to inform policy and intervention development (Capili, 2021). Mixed-methods research is best adopted when real-life, multi-component, experiential perspectives are required to answer the question (National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2018). A solely qualitative methodology would have been equally valuable for this project; however, it would have built on a smaller existing body of literature. Therefore, a mixed-methods approach was selected to highlight mutually insightful information and facilitate comparison with literature across both research types.

2.2 Reflexivity statement

The author is an MSc student physiotherapist and a Nuffield Health ‘Rehabilitation Specialist’, delivering community exercise programmes for people with LTCs. While this aligns with the research focus, Nuffield Health had no involvement in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The author has no affiliations with any named organisations or resources discussed and no qualitative analysis experience beyond MSc Pre-Registration Physiotherapy degree training. Due to the sampling strategy, some participants may know the researcher personally or professionally and may be aware of their background. Personal or professional connections may have influenced participant motivation to take part. These factors are acknowledged as likely shaping the results and conclusions.

2.3 Ethics

The Health and Education Faculty Ethics Committee at Manchester Metropolitan University granted ethical approval (EthOS ID: 72448). An all-in-one access link was created, allowing participants to read the information sheet for informed consent before being asked to provide consent and access the survey. Informed consent involved full disclosure of the study's aims and objectives, risks, benefits, permissions, dissemination and contact information in case of queries or complaints. If any consent questions were declined, participants were excluded from the survey using a logic matrix embedded in the survey design. Participants were free to withdraw at any time during survey completion by closing their web browser; however, withdrawals post-submission were not possible due to the nature of anonymous data collection.

2.4 Participants

Inclusion criteria:

· UK HCPC-registered Physiotherapists and student Physiotherapists with at least one placement experience from any discipline (e.g., musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory) or sector (e.g., public, NHS, private).

· Academic Physiotherapists with valid HCPC registration were also included.

Exclusion criteria:

· Retired Physiotherapists (no HCPC registration).

These inclusion and exclusion criteria were established based on highly comparable related literature (Lowe et al., 2017; Lowe, Littlewood and McLean, 2018; Cunningham and O’Sullivan, 2021a; 2021b) to answer the research question representative of current practices. Students were included because, in recent years, there has been an increased demand to integrate PA promotion into the physiotherapy curriculums globally (Barton et al., 2021) and in the UK (Wing et al., 2025). Therefore, students are considered to have equally important insights as the developing workforce. The research targeted 200 physiotherapists, intending to get a 20% response rate, with an estimated 40 participants suitable for the data processing and analysis.

2.5 Recruitment and Distribution

Participants self-identified (non-probability purposive sampling) from a research summary poster distributed through the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) known as iCSP networks. Permissions were granted in accordance with community rules to post the recruitment poster and message on the Community Rehabilitation iCSP under the ‘News’ heading. The site message included a web link to the survey and a poster featuring a QR code, enabling access across various devices. However, to preserve participant anonymity, no individual follow-up contacts were made. The poster was also available for viewing in the Manchester Metropolitan University study space, the Physiotherapy Department's poster boards and distributed across multiple social media platforms (e.g., X/Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn) from the researcher’s personal accounts. Participants were encouraged to share the survey (snowball sampling) to access hard-to-reach physiotherapists. This combined sampling strategy has been employed in similar published research (Lowe et al., 2017; Stead et al., 2023). The survey was open from 01/02/2025 to 31/03/2025 to allow sufficient participant recruitment.

2.6 Data Collection

2.6.1 Survey Design

Survey questions were established directly from the research objectives and created on the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) platform. There were 30 questions in total; a detailed breakdown of questions can be found in Appendix 1. The survey was estimated at approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. Quantitative questions comprised of closed ‘yes or no’, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale-style questions. A novel assessment was conducted as part of objective 1, using the “Physical Activity: All Our Health” (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022) webpage as a benchmark to evaluate the use of existing government-promoted resources and strategies for implementation. The survey employed techniques to combat survey fatigue and reduce answer bias, such as shuffle-order answers when appropriate and a logic matrix to allow participants to respond to questions only if it applied to them. Qualitative questions were open-text questions with no character limit, supporting the development of ‘thick description’ encouraged in qualitative research. To enhance validity, survey question development literature (Artino et al., 2014; Dillman, Smyth, and Christian, 2014) and survey best practices guidelines (Draugalis, Coons and Plaza, 2008) were followed where possible.

2.6.2 Pilot

The survey questions were informally piloted with a small group of eligible participants. Two members of the University Physiotherapy staff reviewed the survey, providing informed recommendations on its content and formatting during the ethics process. Feedback led to refinement in question order and sentence structure for improved clarity.

2.7 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, percentages) were used to summarise participant demographics and responses relevant to research objectives 1, 2 and 3. Inferential analysis was conducted using Chi-Square (X²) tests of Independence to examine associations between demographic variables and engagement in referral or signpost behaviours for objective 4. Specifically, sector, healthcare setting, years’ experience, and proportion of caseload with LTCs were of interest. ‘Engagement’, for the purpose of this study, was determined by posing the question “Do you signpost and/or refer patients to community physical activity services and/or information?” with ‘yes or no’ responses as possible answers. To complement the X² statistic, Cramér’s V measure of effect size was used to add context (strength of association) to the findings. All quantitative data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel, version 2503.

Qualitative components were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis, following the six-phase framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). An inductive coding approach was applied, with codes and themes developed directly from the data by the sole researcher. Coding and thematic development were iterative, with themes refined throughout the data collection and analysis phases. Data saturation was considered throughout the coding process. Although surveys do not allow for theoretical saturation like interviews or focus groups, the analysis continued until no new codes or patterns emerged from the qualitative responses, indicating sufficient thematic saturation for this study. A reflexive journal was used throughout to document biases and assumptions during interpretation.

Quantitative and qualitative findings are reported sequentially and grouped according to their respective objective to support a mixed-methods interpretation and triangulation during discussion.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Demographics

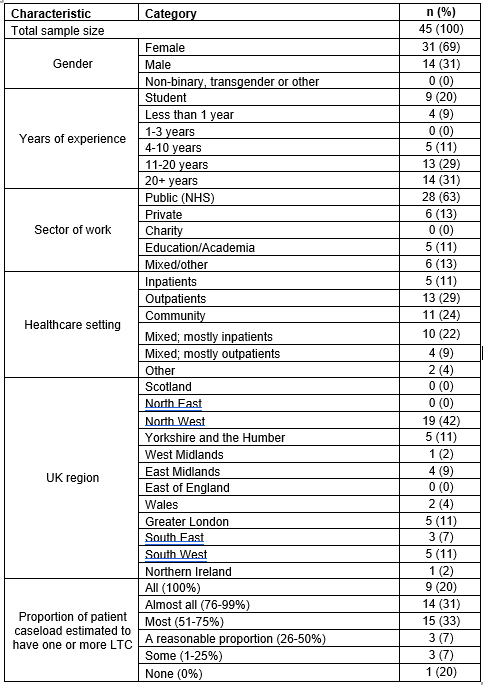

Forty-five eligible participants completed the survey (22.5% response rate), comprising of 36 qualified physiotherapists and 9 student physiotherapists. Demographic information is presented in Table 1. The sample consisted of participants from 9 different UK regions, with 69% being female and a mean age (standard deviation) of 37.8 (10.6) years. Thirty-one percent had over 20 years of experience as physiotherapists, 63% were from the public sector (NHS), and 29% worked in outpatient settings. Those who selected “Mixed/Other” sectors provided further clarification through open-text responses. Of these, 2 participants indicated working across the NHS and private sectors, 3 reported mixed sector experience (e.g., students undertaking placements across various sectors), and 1 reported working in both education and charity sectors. For healthcare settings, 2 participants selected “Mixed/Other” where 1 reported working in academia exclusively and 1 in an emergency frailty service. Eighty-four percent of physiotherapists in this study reported that a majority of their patient caseload consisted of patients with one or more LTCs.

Table 1: Participant Demographics

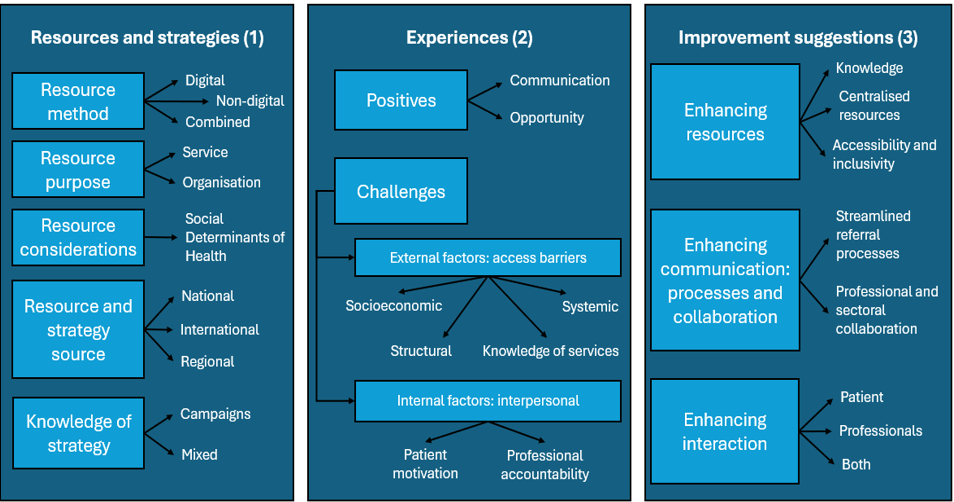

3.2 Thematic analysis summary

Five themes and 11 sub-themes were generated for objective 1, 2 themes and 8 sub-themes for objective 2, and 3 themes and 8 sub-themes for objective 3. Figure 1 summarises the analysis via coding tree. Appendix 2 contains a table of each theme, sub-theme, and code with examples.

Figure 1: Thematic coding tree

3.3 Objective 1: Current resources and strategies and familiarity of existing government tools

3.3.1 Quantitative findings

Ninety-three percent of participants reported that they prescribe PA in their role, 49% refer patients to PA services, 51% signpost to PA opportunities or information, and only 1 participant did not do any. Eleven percent chose ‘Other’, reporting discussing PA within academic roles or engaging patients in PA education. Seventy-six percent stated they refer or signpost to community PA services or information in their practice. Of these, 88% reported that they or their team use resources, but only 29% have strategies to refer or signpost to community PA services or information.

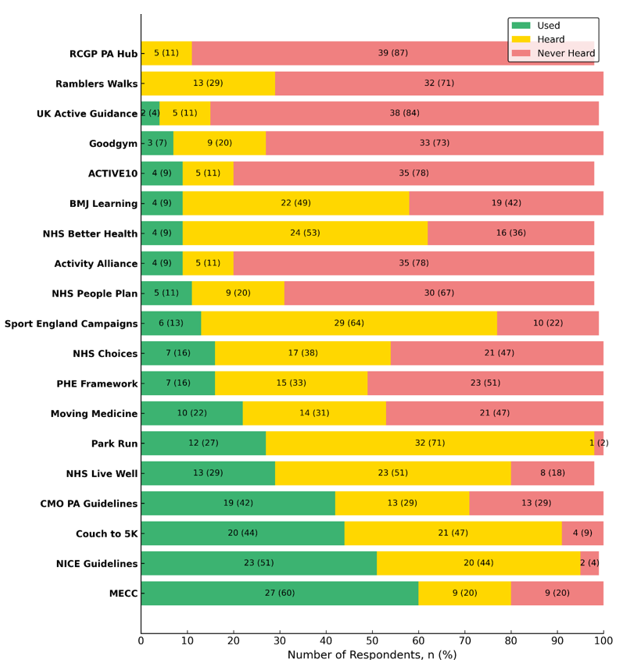

The most well-known resource/strategy from the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022) ‘Physical Activity: Applying All Our Health’ was the MECC initiative. Other well-known resources included Couch to 5K, the NICE and the UK CMO Guidelines. The largely unknown resources and strategies included the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) PA Hub, UK Active: Moving at Scale Guidance, ACTIVE10 and Activity Alliance. Despite being heard of, the RCGP PA Hub and Ramblers Walks were not used at all in practice. Park run had the greatest discrepancy between participants who knew of it but did not use it in their practice, with only 1 participant never having heard of it. Figure 2 summarises this, detailing the percentages of participants who use it in clinical practice, and whether they are aware of it or not. Resources and strategies are listed in descending order of 'Used' responses for readability.

Figure 2. Participants' familiarity of government-promoted resources and strategies

Note. Bars represent number and percentage of respondents who selected each category. Full resource/strategy names: MECC = Make Every Contact Count; CMO PA Guidelines = UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines; NICE Guidelines = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines for PA; PHE Framework = Public Health England: Everybody active, every day; RCGP PA Hub = Royal College of General Practitioners Physical Activity Hub; BMJ Learning = British Medical Journal e-learning modules.

3.3.2 Qualitative findings

Thematic analysis revealed 5 key themes: resource method, purpose, considerations, resource and strategy source, and knowledge of strategies as presented in Table 2. Participants described a wide variety of resources, most commonly digital or printed formats. Websites and leaflets were preferred for accessibility and ease of use, while social prescribing and professional networking enhanced person-centred referral strategies. Resources were selected with patient context in mind, particularly where digital exclusion or cultural needs were considered. While formal strategies were less commonly known, a few participants identified community-led campaigns and NHS frameworks as useful anchors for action.

Table 2. Resources and strategies used to support referral or signpost

3.4 Objective 2: Physiotherapist experiences to refer or signpost to community PA services or information.

3.4.1 Quantitative findings

When participants were asked about their experience when trying to refer or signpost to community PA services or information, 20% reported a positive experience, 42% reported that they faced challenges, and 38% reported that they had a mixed experience.

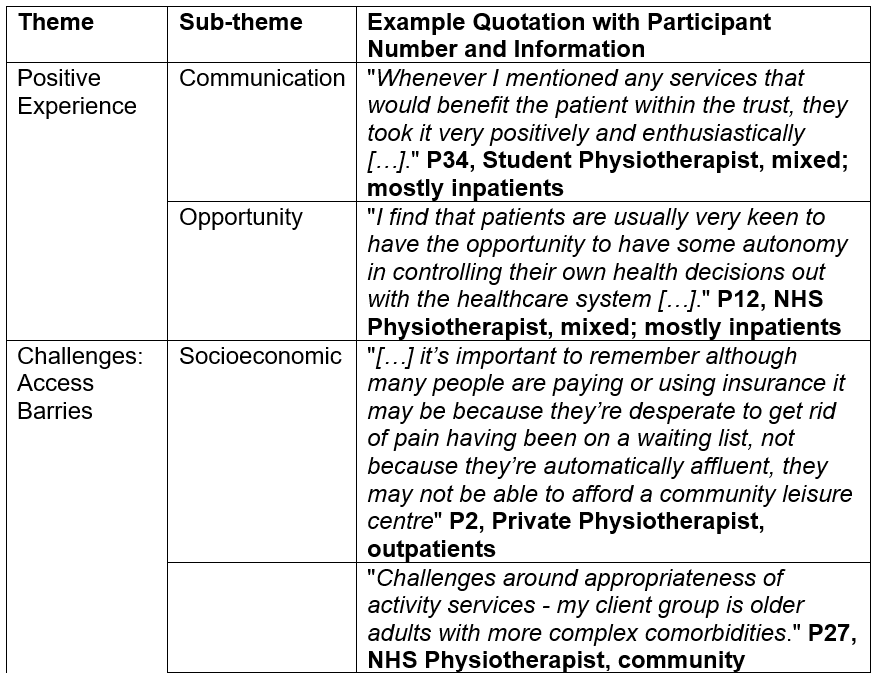

3.4.2 Qualitative findings

Participants described a range of experiences when attempting to refer or signpost patients to community PA services. Two overarching themes were identified: positive experiences with 2 sub-themes and challenges with 6 sub-themes, the latter being more frequently discussed, presented in Table 3. While some participants described positive experiences facilitated by supportive teams, motivational interviewing, or embedded pathways, many highlighted substantial barriers. These included accessibility issues related to geography and affordability, difficulties with complex or time-consuming referral systems, and a notable lack of awareness or training around existing services. Students especially felt underprepared. Additional barriers included limited patient motivation and a sense among some physiotherapists that community PA referrals were not part of their professional remit or that their practice setting made such referrals impractical.

Table 3. Physiotherapist experiences of referral or signpost

3.5 Objective 3: Perceived effectiveness of resources and strategies used to refer or signpost and exploration of way to improve referral and signpost.

3.5.1 Quantitative findings

Figure 3 shows participants’ views on the effectiveness of the resources and strategies they described. Most participants reported that their described resources and strategies were moderately effective in improving referral or signposting to community PA services or information.

Figure 3. Participants’ perceived effectiveness of referral and signposting resources and strategies (n = 45, 100%)

3.5.2 Qualitative findings

Three overarching themes emerged regarding improving these practices: enhancing resources with 3 sub-themes, communication with 2 sub-themes, and interaction with 3 sub-themes, presented in Table 4. Participants suggested multiple ways to improve signposting and referral practices. The need for improved awareness and knowledge of existing services was a central concern, with participants calling for clearer, more centralised, and up-to-date directories. Several mentioned the value of tailored Continuous Professional Development (CPD) or in-person training opportunities. Digital solutions like streamlined referral forms and searchable online platforms were commonly recommended. Barriers such as lack of time and disconnected professional pathways were also highlighted, suggesting that both organisational infrastructure and collaborative networks need development. Improving patient accessibility was also emphasised through inclusive design, targeted support, and better advertising.

Table 4. Suggested improvements to referral and signposting practice

3.6 Objective 4: Associations between demographic factors and engagement in referral or signposting

Four X² tests of Independence were completed between demographic factors of interest and engagement in referral or signpost practices, presented in Table 5. No significant associations between demographic factors and engagement were found for the physiotherapy sector, setting or years practiced. However, a significant association was found for the proportion of patient caseload with LTCs. Cramér V’s effect size of association revealed all associations were moderate-to-strong (0.4 -0.5) in strength except for sector, which was minimal (<= 0.2).

Table 5. X² tests of Independence and Cramér’s V statistics

4. Discussion

This study explored the resources and strategies used by UK physiotherapists and students to refer or signpost to community PA services and information, and captured their experiences to better understand current implementation. Participant demographics closely align with existing literature (Lowe et al., 2017; Wing et al., 2025), supporting transferability within UK settings, particularly England. However, due to limited representation in some regions and a small sample size, the findings are not generalisable, and quantitative results should be interpreted with caution.

The results revealed a clear gap between promoting PA and formally engaging with structured implementation methods. Although 93% of participants reported prescribing PA, only 49% referred and 51% signposted patients to PA services or information. In total, 76% used either referral or signposting approaches. However, a notable contrast emerged between the use of PA resources and defined strategies—supportive tools were relatively common, while structured methods remained underused. This reflects findings from Stead et al. (2023) and Wing et al. (2025), who noted that although PA promotion is seen as integral to practice, confidence and consistency in using formal referral pathways is limited. Similarly, Robinson et al. (2023) found that Allied Health Professionals (AHPs), including physiotherapists, lacked confidence and clarity on how and where to refer, a result echoed strongly in this study’s qualitative findings.

The qualitative findings helped explain the quantitative gap, offering insight into how resources are applied in practice. Participants described a wide range of tools used to support signposting, including digital resources such as national websites, NICE guidelines, and online repositories. Physical materials—especially leaflets—were frequently mentioned, particularly when directing patients to local PA opportunities. Resource selection was often tailored to individual patient needs, especially for those facing digital exclusion, language or literacy barriers, or living with complex/multiple LTCs. Carstairs et al. (2020) found that patients tend to prefer local, tangible resources over generic online content, which may explain clinicians’ preference for these formats beyond their practicality. Similarly, Cantrell et al. (2024) reported that brief signposting tools are less effective unless integrated into relational, personalised support structures like care pathways.

Despite the wide availability of public health and PA promotion tools in the UK, awareness of government-promoted methods was limited. While strategies like MECC and resources like the NICE PA guidelines were relatively well known and used, others showed surprisingly low recognition. This suggests many tools fail to reach frontline practice, despite policy emphasis and investment. Some variation in awareness is expected—for instance, the RCGP PA Hub may be less familiar to AHPs due to its primary focus on General Practitioners. Additionally, not all resources listed in the Physical Activity: Applying All Our Health guidance (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022) are applicable to patients with LTCs, limiting its use as a benchmark for this population. Much of PA promotion policy language is shifting away from condition-specific guidance and focusing on getting more people moving in any way they can (Department of Health and Social Care, 2019; WHO, 2018a; 2018b; 2020), reducing fear-related barriers around movement. It is debatable whether this new language is wise for those with LTCs, but new evidence would suggest so (Dibbens et al., 2024). To the author’s knowledge, prior to this project, no UK-based study has quantitatively assessed physiotherapists’ familiarity with specific named government-promoted PA resources and strategies, marking a small-scale but novel contribution. Cunningham and O’Sullivan (2021b), in the closest relevant study based in Ireland and Northern Ireland, identified general resource sources for knowledge development rather than named public tools or implementation supports. Their sample included other professionals such as GPs, offering breadth but less relevance for UK physiotherapy specifically. They found that over 90% of participants used government health websites as information sources, though awareness of named resources was unclear. While their work (Cunningham and O’Sullivan, 2021a; b) offers important insight into clinician behaviour and systemic supports, this study builds on it by assessing actual use versus awareness of named government tools. These findings echo Vishnubala and Pringle (2021), who reported a disconnect between available policy resources and clinician awareness. Whether this gap stems from a lack of appropriate resources or poor uptake remains unclear—this study suggests the latter is likely.

Cantrell et al. (2024) provide a valuable rapid realist review of how signposting is implemented, understood, and resourced across UK health and care settings. Their findings align with this study, highlighting the inconsistency of signposting delivery, the need for provider training, and the importance of reliable, up-to-date directories. While Cantrell et al. (2024) take a system-level, theoretical approach, the present study complements this by offering grounded, profession-specific insight from physiotherapy practice. Together, the findings point to a persistent gap between policy and frontline implementation, underlining the need for a clearer, better-supported signposting infrastructure for promoting PA among patients with LTCs. A central question remains: should referral and signposting be used reactively to relieve primary care pressures, or should they be integrated into care pathways from the outset? Current UK strategies do not clarify this distinction and overlook the complexity of implementation in practice.

Participants’ experiences of referral and signposting varied widely. Only 20% described the process positively, while 42% reported challenges. Common issues included complex or inconsistent referral processes, regional disparities in service availability, low confidence in external providers, and unclear responsibility for who should initiate referral or signposting within clinical pathways. Student physiotherapists, in particular, reported feeling under-supported. These issues reflect themes in existing literature: Dunphy et al. (2024) noted that clinicians often face systemic barriers, such as poor integration and limited feedback, when navigating community referrals for patients with LTCs. Similarly, Speake et al. (2021) identified organisational constraints—time, service awareness, and professional boundaries—that hinder implementation. This study reinforces the view that while clinicians want to promote PA, they lack systemic support and structure to do so. This raises further questions about how leadership plans to address the gap without investing in better resources and strategies to tackle this. As the Darzi report (2024) emphasises, meaningful progress will require a reallocation of focus, funding, and coordinated effort to foster collaboration across sectors, services, and clinicians toward a community-focused care model.

Although many participants viewed their current signposting approaches as moderately effective, qualitative responses revealed a strong desire for improvement. Numerous suggestions included creating a centralised, up-to-date database of local and national PA services, expanding access to CPD or formal training, simplifying referral forms, and improving communication between social prescribers, community partners, and clinicians. These ideas reflect a clear call for a more coherent and better-supported infrastructure for PA referral and signposting. These preferences align with Cantrell et al. (2024), who found that frontline providers need confidence in local service quality, accurate directories, and support in matching services to patient needs. Similarly, Robinson et al. (2023) reported that 60% of AHPs wanted more formal training and resources to aid PA promotion, though their study’s single-centre scope limits generalisability. Further research is needed to explore how a national database could function in practice, acknowledging the significant challenges its development may entail.

Lastly, while sector, setting, and years of experience showed no significant association with referral or signposting behaviour, physiotherapists with a higher proportion of patients with LTCs were significantly more likely to engage in these practices. This suggests that clinical relevance, rather than professional demographics, may better predict implementation behaviour. These findings offer insight into who is driving this work and could guide future inclusion criteria to capture relevant perspectives. Future studies may benefit from broad inclusion across sectors and experience levels, while specifically targeting those with high LTC caseloads to enhance applicability.

4.1 Methodological Limitations

Like all research, this study has several methodological considerations. First, as a cross-sectional observational design, results should be interpreted with caution and do not imply causality. The limited sample size means findings cannot quantify prevalence in the way epidemiological studies can. This study does not offer a comprehensive list of UK-wide resources, evaluate their effectiveness, or resolve the implementation challenges discussed.

Second, the response rate may be contested. Following Draugalis, Coons, and Plaza’s (2008) best practice guidance, the survey—primarily distributed through the iCSP ‘Community Rehabilitation’ network (approx. 2,484 members)—yielded a 1.81% response rate. Based on the broader UK population of physiotherapists and students (82,428 total: 75,744 physiotherapists [HCPC, 2025] and 6,684 students [CSP, 2021]), the response rate was 0.055%. However, the true rate is unclear due to additional recruitment via social media, snowball sampling, and the difficulty in estimating the eligible student population. Despite this, the sample size was sufficient for X²analysis and suited the aims of this study.

Third, several best-practice elements were omitted due to ethical, practical, and feasibility constraints, including individual follow-ups, formal pilot testing, survey psychometric evaluation, and random probability sampling. Outliers were not discussed despite its mention in the COREQ recommendations due to irrelevance. Additionally, the survey missed the opportunity to ask why some participants do not refer or signpost, limiting insights into barriers and weakening the analysis for Objectives 2 and 3. The study also unintentionally omitted region-specific resources for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, referencing only existing England-specific tools. Single-author thematic analysis introduces bias, as interpretation lacks external validation. While thematic content analysis could have strengthened mixed-method triangulation, it was not included in the research proposal and thus not conducted. Another major omission is the patient voice. Lowe et al. (2016) scoping review identified this gap, noting practical barriers often exclude patient perspectives. Yet meaningful, lasting change requires input from all stakeholders. Future research should involve service users—perhaps through co-designed methodologies—to explore how community PA referral is not only delivered but received and understood.

Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into the real-world implementation of PA referral and signposting among UK physiotherapists and contributes to the growing evidence base calling for improved tools, integration, and training to support clinical health promotion.

4.2 Future research recommendations

Based on triangulated findings and existing literature, future research should include larger-scale surveys to assess regional variation and link awareness trends to commissioning practices. In-depth qualitative inquiry into student preparedness, team-based approaches, and patient preferences could support the development of co-produced tools between clinicians and patients. Randomised controlled trials are needed to evaluate the actual effectiveness - beyond perceived effectiveness - of different resource types (e.g. digital, print, social referral) in promoting patient uptake, especially across diverse LTC populations. Mixed-method development of tools such as decision matrices to guide clinicians in tailoring PA promotion based on patient suitability would support more inclusive, equitable care and practical implementation. Finally, greater clarity is needed around leadership responsibility for PA promotion within UK physiotherapy, particularly from a preventative policy standpoint, to improve strategy and accountability.

5. Conclusion

Shifting towards a preventative healthcare model is important and wanted by many, but it isn't easy to realise. This study aimed to extend existing quantitative and qualitative research by exploring how UK physiotherapists refer or signpost patients with LTCs to community PA. Using a mixed-methods approach, the quantitative findings revealed clear discrepancies between PA prescription and referral/signposting practices, along with limited awareness of existing government-promoted resources and strategies. Qualitative data supported these findings, highlighting the need to improve current practices by addressing known barriers and enhancing resources, processes, collaboration, and engagement.

While this study reinforces themes from existing literature, critical gaps remain—particularly the disconnect between policy ambitions and real-world implementation. Physiotherapists in this study called for collated and improved resources and strategies to enhance referral and signpost to community PA for those with LTCs. Greater clarity from physiotherapy authorities is needed to establish effective strategies, frameworks, and tools to guide clinicians. This research also supports the development of a national database to improve clinicians’ recognition of local and national community PA opportunities, though responsibility for this remains unclear. More pragmatic and solution-driven research is required to change the clinical landscape to fulfil the shift towards a preventative healthcare model and reap its benefits.

6. References

Albert, F.A., Crowe, M.J., Malau-Aduli, A.E.O. and Malau-Aduli, B.S. (2020) ‘Physical activity promotion: a systematic review of the perceptions of healthcare professionals’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4358. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124358.

Alsop, T., Woodforde, J., Rosbergen, I., Mahendran, N., Brauer, S. and Gomersall, S. (2023) ‘Perspectives of health professionals on physical activity and sedentary behaviour in hospitalised adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis’, Clinical Rehabilitation, 37(10), pp. 1386–1405. doi: 10.1177/02692155231170451.

Artino, A.R. Jr, La Rochelle, J.S., Dezee, K.J. and Gehlbach, H. (2014) ‘Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87’, Medical Teacher, 36(6), pp. 463–474. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889814.

Barton, C.J., King, M.G., Dascombe, B., Taylor, N.F., de Oliveira Silva, D., Holden, S., Goff, A.J., Takarangi, K. and Shields, N. (2021) ‘Many physiotherapists lack preparedness to prescribe physical activity and exercise to people with musculoskeletal pain: a multi-national survey’, Physical Therapy in Sport, 49, pp. 98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2021.02.002.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp. 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Cantrell, A., Booth, A., Timmons, S., Thompson-Coon, J., Taylor, M., Duncan, E., Shaw, R., Hunter, R., Martyn St James, M., Woods, H.B., Waddington, C., Rodgers, M., Sowden, A. and Goyder, E. (2024) Signposting services for people with health and social care needs: a realist synthesis. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library. doi: 10.3310/GART5103.

Capili, B. (2021) ‘Cross-sectional studies’, American Journal of Nursing, 121(10), pp. 59–62. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000794280.73744.fe.

Carstairs, S.A., Rogowsky, R.H., Cunningham, K.B., Sullivan, F. and Ozakinci, G. (2020) ‘Connecting primary care patients to community-based physical activity: a qualitative study of health professional and patient views’, BJGP Open, 4(3), bjgpopen20X101100. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101100.

Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) (2021) Diversity data 2021: equity, diversity and belonging. Available at: https://www.csp.org.uk/about-csp/equity-diversity-belonging/member-data/diversity-data-2021 (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

Clifford, R. (2018) ‘Promoting physical activity for health. A survey of knowledge, confidence and role-perception in final-year UK physiotherapy students’, Physiotherapy Practice and Research, 39, pp. 53–62.

Cunningham, C., and O’Sullivan, R. (2021a) ‘Healthcare Professionals’ Application and Integration of Physical Activity in Routine Practice with Older Adults: A Qualitative Study’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11222. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111222

Cunningham, C. and O’Sullivan, R. (2021b) ‘Healthcare Professionals’ Promotion of Physical Activity with Older Adults: A Survey of Knowledge and Routine Practice’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6064. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116064.

Darzi, A. (2024) Independent investigation of the national health service in England. Open Government Licence. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-investigation-of-the-nhs-in-england (Accessed on 15/03/2024).

Dennis, S., Kwok, W., Alison, J., Hassett, L., Nisbet, G., Refshauge, K., Sherrington, C. and Williams, A. (2024) ‘How effective are allied health group interventions for the management of adults with long-term conditions? An umbrella review of systematic reviews and its applicability to the Australian primary health system’, BMC Primary Care, 25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02570-7 (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Department of Health and Social Care (2019) UK Chief Medical Officers' physical activity guidelines. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report (Accessed: 10 November 2024).

Dibben, G.O., Gardiner, L., Young, H.M.L., Wells, V., Evans, R.A., Ahmed, Z., Barber, S., Dean, S., Doherty, P., Gardiner, N., Greaves, C., Ibbotson, T., Jani, B.D., Jolly, K., Mair, F.S., McIntosh, E., Ormandy, P., Simpson, S.A., Ahmed, S., Krauth, S.J., Steell, L., Singh, S.J. and Taylor, R.S. (2024) ‘Evidence for exercise-based interventions across 45 different long-term conditions: an overview of systematic reviews’, EClinicalMedicine, 72, 102599. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102599.

Dillman, D.A., Smyth, J.D. and Christian, L.M. (2014) Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 4th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Draugalis, J.R., Coons, S.J. and Plaza, C.M. (2008) ‘Best practices for survey research reports: a synopsis for authors and reviewers’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(1), 11. doi: 10.5688/aj720111.

Dunphy, R. and Blane, D.N. (2024) ‘Understanding exercise referrals in primary care: a qualitative study of general practitioners and physiotherapists’, Physiotherapy, 124, pp. 1–8.

Flannery, C., Dennehy, R., Riordan, F., Cronin, F., Moriarty, E., Turvey, S., O'Connor, K., Barry, P., Jonsson, A., Duggan, E., O’Sullivan, L., O'Reilly, É., Sinnott, S.-J. and McHugh, S. (2022) ‘Enhancing referral processes within an integrated fall prevention pathway for older people: a mixed-methods study’, BMJ Open, 12, e056182. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056182.

Franco, M.R., Tong, A., Howard, K., Sherrington, C., Ferreira, P.H., Pinto, R.Z. and Ferreira, M.L. (2015) ‘Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(19), pp. 1268–1276. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015.

Freene, N., Cools, S. and Bissett, B. (2017) ‘Are we missing opportunities? Physiotherapy and physical activity promotion: a cross-sectional survey’, BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 9, 19. doi: 10.1186/s13102-017-0084-y.

Gavin, J.P., Clarkson, P., Muckelt, P.E., Eckford, R., Sadler, E., McDonough, S. and Barker, M. (2024) ‘Healthcare professional and commissioners’ perspectives on the factors facilitating and hindering the implementation of digital tools for self-management of long-term conditions within UK healthcare pathways’, PLOS ONE, 19(8), e0307493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0307493.

Greenwood-Lee, J., Jewett, L., Woodhouse, L. and Marshall, D.A. (2018) ‘A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care’, BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 986. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y.

Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (2023) Standards of proficiency: Physiotherapists – Standard 15. Available at: https://www.hcpc-uk.org/standards/standards-of-proficiency/physiotherapists/ (Accessed: 12 April 2025).

Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (2025) Registrant snapshot: January 2025. Available at: https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/data/2025/registrant-snapshot-january-2025/ (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

Honeyman, M., Dunn, P. and McKenna, H. (2016) A digital NHS? An introduction to the digital agenda and plans for implementation. London: The King’s Fund. Available at: https://www.abhi.org.uk/media/1210/a_digital_nhs_kings_fund_sep_2016.pdf (Accessed: 11 December 2024).

Hopman, P., de Bruin, S.R., Forjaz, M.J., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Tonnara, G., Lemmens, L.C., Onder, G., Baan, C.A. and Rijken, M. (2016) ‘Effectiveness of comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions or frailty: a systematic literature review’, Health Policy, 120(7), pp. 818–832. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.002.

Jones, K. and Burns, A. (2021) Costs of health and social care 2021. Personal Social Services Research Unit. Available at: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/92342/25/Unit%20Costs%20Report%202021%20-%20Final%20version%20for%20publication%20%28AMENDED2%29.pdf (Accessed: 5 December 2024).

Kunstler, B., Fuller, R., Pervan, S. and Merolli, M. (2019) ‘Australian adults expect physiotherapists to provide physical activity advice: a survey’, Journal of Physiotherapy, 65, pp. 230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.004.

Lowe, A., Gee, M., Littlewood, C., Mclean, S., Lindsay, C. and Everett, S. (2016) ‘Physical activity promotion in physiotherapy practice: a systematic scoping review of a decade of literature’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(2), pp. 122–127.

Lowe, A., Littlewood, C., McLean, S. and Kilner, K. (2017) ‘Physiotherapy and physical activity: a cross-sectional survey exploring physical activity promotion, knowledge of physical activity guidelines and the physical activity habits of UK physiotherapists’, BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine, 3, e000290. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2017-000290.

Lowe, A., Littlewood, C. and McLean, S. (2018) ‘Understanding physical activity promotion in physiotherapy practice: A qualitative study’, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 35, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.01.009.

Moffatt, S., Wildman, J., Pollard, T.M., Gibson, K., Wildman, J.M., O’Brien, N., Griffith, B., Morris, S.L., Moloney, E., Jeffries, J., Pearce, M. and Mohammed, W. (2023) ‘Impact of a social prescribing intervention in North East England on adults with type 2 diabetes: the SPRING_NE multimethod study’, Public Health Research, 11(2). doi: 10.3310/aqxc8219.

Moran, H. (2017) ‘Public health: physical activity – the unique role for physiotherapists’, Shift Learning, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Available at: https://www.csp.org.uk/system/files/csp_public_health_report_presentation.pdf (Accessed: 5 December 2024).

Mossabir, R., Morris, R., Kennedy, A., Blickem, C. and Rogers, A. (2015) ‘A scoping review to understand the effectiveness of linking schemes from healthcare providers to community resources to improve the health and well-being of people with long-term conditions’, Health and Social Care in the Community, 23, pp. 467–484. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12176.

National Health Service (2019) The NHS long term plan. NHS England. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (Accessed: 7 January 2019).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care (PH44). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44 (Accessed: 10 March 2025).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities (NG44). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng44 (Accessed: 10 March 2025).

National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (2018) Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health. Available at: https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/Best_Practices_for_Mixed_Methods_Research.pdf (Accessed: 10 March 2025).

Omotayo, O., Maduka, C.P., Muonde, M., Olorunsogo, T.O. and Ogugua, J.O. (2024) ‘The rise of non-communicable diseases: a global health review of challenges and prevention strategies’, International Medical Science Research Journal, 4, pp. 74–88. doi: 10.51594/imsrj.v4i1.738.

Parchment, A., Lawrence, W., Rahman, E., Townsend, N., Wainwright, E. and Wainwright, D. (2022) ‘How useful is the Making Every Contact Count Healthy Conversation Skills approach for supporting people with musculoskeletal conditions?’, Journal of Public Health, 30(10), pp. 2389–2405.

Public Health England (PHE) (2020) Health matters: physical activity – prevention and management of long-term conditions. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-physical-activity/health-matters-physical-activity-prevention-and-management-of-long-term-conditions (Accessed: 12 November 2024).

Qiu, Y., Fernández-García, B., Lehmann, H.I., Li, G., Kroemer, G., López-Otín, C. and Xiao, J. (2023) ‘Exercise sustains the hallmarks of health’, Journal of Sport and Health Science, 12(1), pp. 8–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2022.10.003.

Raghavan, A., Vishnubala, D., Iqbal, A., Hunter, R., Marino, K., Eastwood, D., Nykjaer, C. and Pringle, A. (2023) ‘UK nurses delivering physical activity advice: what are the challenges and possible solutions? A qualitative study’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(23), 7113. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20237113.

Reddy, R.S., Alahmari, K.A., Alshahrani, M.S., Alkhamis, B.A., Tedla, J.S., Almohiza, M.A., Elrefaey, B.H., Koura, G.M., Gular, K., Alnakhli, H.H., Mukherjee, D., Rao, V.S. and Al-Qahtani, K.A. (2024) ‘Exploring the impact of physiotherapy on health outcomes in older adults with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional analysis’, Frontiers in Public Health, 12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1415882 (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Reid, H., Ridout, A.J., Tomaz, S.A., Kelly, P., Jones, N. and the Physical Activity Risk Consensus Group (2022) ‘Benefits outweigh the risks: a consensus statement on the risks of physical activity for people living with long-term conditions’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(8), pp. 427–438. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104281.

Sharma, A., Minh Duc, N.T., Luu Lam Thang, T., Nam, N.H., Ng, S.J., Abbas, K.S., Huy, N.T., Marušić, A., Paul, C.L., Kwok, J., Karbwang, J., De Waure, C., Drummond, F.J., Kizawa, Y., Taal, E., Vermeulen, J., Lee, G.H.M., Gyedu, A., To, K.G., Verra, M.L., Jacqz-Aigrain, É.M., Leclercq, W.K.G., Salminen, S.T., Sherbourne, C.D., Mintzes, B., Lozano, S., Tran, U.S., Matsui, M. and Karamouzian, M. (2021) ‘A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS)’, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(10), pp. 3179–3187.

Skinner, G. and Clemence, M. (2017) Ipsos MORI Veracity Index 2017. Cited in: UK Health Security Agency (2018) It’s good to talk: making the most of our conversations, UKHSA blog, 8 January. Available at: https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2018/01/08/its-good-to-talk-making-the-most-of-our-conversations/ (Accessed: 9 March 2025).

Sloggett, R. (2023) The forgotten majority? A new policy framework for improving outcomes for people with long-term conditions. London: Future Health. Available at: https://www.futurehealth-research.com/ (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Speake, H., Copeland, R., Breckon, J. and Till, S. (2021) ‘Challenges and opportunities for promoting physical activity in health care: a qualitative enquiry of stakeholder perspectives’, European Journal of Physiotherapy, 23(3), pp. 157–164. doi: 10.1080/21679169.2019.1663926.

Stead, A., Vishnubala, D., Marino, K.R. and others (2023) ‘UK physiotherapists delivering physical activity advice: what are the challenges and possible solutions? A qualitative study’, BMJ Open, 13, e069372. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069372.

The Health Foundation (2018) Understanding the health care needs of people with multiple health conditions. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2018/Understanding%20the%20health%20care%20needs%20of%20people%20with%20multiple%20health%20conditions.pdf (Accessed: 11 February 2025).

Thomas, W., Wright, M. and Chesterton, P. (2025) ‘Student and physiotherapists' perceived abilities to prescribe effective physical activity and exercise interventions: a cross-sectional survey’, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 75, 103245. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2024.103245.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. and Craig, J. (2007) ‘Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups’, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), pp. 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Vodovotz, Y., Barnard, N., Hu, F.B., Jakicic, J., Lianov, L., Loveland, D., Buysse, D., Szigethy, E., Finkel, T., Sowa, G., Verschure, P., Williams, K., Sanchez, E., Dysinger, W., Maizes, V., Junker, C., Phillips, E., Katz, D., Drant, S., Jackson, R.J., Trasande, L., Woolf, S., Salive, M., South-Paul, J., States, S.L., Roth, L., Fraser, G., Stout, R. and Parkinson, M.D. (2020) ‘Prioritised research for the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease: recommendations from the Lifestyle Medicine Research Summit’, Frontiers in Medicine, 7. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.585744.

West, K., Purcell, K., Haynes, A., Taylor, J., Hassett, L. and Sherrington, C. (2021) ‘“People associate us with movement so it’s an awesome opportunity”: perspectives from physiotherapists on promoting physical activity, exercise and sport’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2963. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062963.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (1998) Health promotion glossary. Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/64546/WHO_HPR_HEP_98.1.pdf (Accessed: 12 December 2024).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018a) Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514187 (Accessed: 10 October 2024).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018b) More active people for a healthier world: draft global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030. Report by the Director-General. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276366 (Accessed: 10 October 2024).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (Accessed: 10 October 2024).